- US regulators have authorized a second coronavirus vaccine for emergency use.

- This two-dose vaccine, developed by the biotech firm Moderna and the US National Institutes of Health, was about 94% effective at preventing COVID-19 in a large clinical trial.

- Moderna’s vaccine is easier to store and transport than Pfizer’s COVID-19 shot, which got US clearance a week ago.

- Moderna plans to deliver 20 million doses in the US by year’s end.

- The authorization is the latest achievement in a remarkable story of science and business for Moderna, a company that has surged in 2020 based off its COVID-19 success.

- For more stories like this, sign up here for Business Insider’s daily healthcare newsletter.

The US Food and Drug Administration authorized Moderna’s coronavirus shot for emergency use, making the two-dose vaccine the second to be cleared by US regulators.

Moderna’s vaccine can be given to all people in the US over age 18, the FDA said Friday in a news release. The authorization comes a day after an independent panel of experts recommended that FDA greenlight the shot.

The authorization will boost the US supply of a crucial pandemic-fighting tool, and Moderna’s shot is easier to ship and store than the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. Within days, the US government’s Operation Warp Speed vaccine initiative plans to ship out 5.9 million doses of Moderna’s shot to more than 3,200 sites across the nation.

Having two authorized vaccines should allow tens of millions of Americans to get vaccinated in the coming months. Warp Speed officials anticipate 20 million Americans will get a shot in December, 30 million more in January, and 50 million more in February.

“With the availability of two vaccines now for the prevention of COVID-19, the FDA has taken another crucial step in the fight against this global pandemic that is causing vast numbers of hospitalizations and deaths in the United States each day,” FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn said in a news release.

Healthcare workers and people living in nursing homes are being vaccinated first. Plans vary by state, but essential workers such as teachers and firefighters are generally next in line. Top government scientists, including Dr. Anthony Fauci and Warp Speed chief advisor Moncef Slaoui, have said vaccines should be available to the general public in late-spring or early summer. They hope that will help the US return to some level of normality in the summer or fall.

Steven Ferdman/Getty Images

Like Pfizer's vaccine, Moderna's injection excels at preventing COVID-19. A late-stage clinical trial of the shot enrolled more than 30,000 volunteers and determined that Moderna's shot was safe and 94% effective at preventing symptomatic disease. It also appeared to be very good at preventing severe disease, with 30 severe illnesses reported among people who got placebo injections and zero among those who got Moderna's vaccine.

A key advantage of Moderna's shot is that it's easier to ship and store.

The first US-authorized vaccine, developed by Pfizer and the German biotech company BioNTech, needs to be stored at negative 94 degrees Fahrenheit, a logistical challenge for the existing healthcare infrastructure. In contrast, Moderna's vaccine is stable for a month with typical refrigeration, avoiding the need for extra-cold freezers and dry ice.

That flexibility could make it easier for Moderna's shot to reach more places, particularly rural parts of the country. That difference can be seen in the rollout: Moderna's shot will be shipped to about five times as many locations as Pfizer's initial shipment.

AP Photo/Evan Vucci

Even with unprecedented success, mammoth challenges lie ahead

Work on coronavirus vaccines is far from over. The biggest challenges now become mass-producing the vaccines, distributing them around the world, and convincing people to get the shots.

Low- and middle-income countries are likely to struggle the most in getting access, particularly to these first vaccines. Pfizer and Moderna have struck dozens of supply deals with countries around the world, committing to sell their limited quantities of doses.

While the World Health Organization has developed an initiative called Covax that will attempt to not leave the developing world behind, the actual impact of that program remains murky.

The US isn't participating in Covax. Instead, Warp Speed has lined up supply deals with six vaccine-makers to secure 900 million doses for the US, with contract options to boost that figure to up to 3 billion doses, Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said on a December 16 call with reporters.

Nearly one in four people in the world may not be able to get a COVID-19 vaccine until at least 2022, Johns Hopkins University researchers found in a recent analysis published in The BMJ.

Ramping up manufacturing is also a challenge facing both Pfizer and Moderna. In November, Pfizer was forced to cut its supply projection by 50%, down to 50 million doses for 2020, stemming from supply-chain and manufacturing difficulties.

While Moderna has reaffirmed it's on track to deliver 20 million doses by the end of 2020, it has given a wide-ranging estimate for next year. The company plans to produce between 500 million and 1 billion doses in 2021. Both companies' vaccines can be tricky to manufacture.

Taimy Alvarez/AP

Adding to the challenge, Moderna has never before mass-produced a medicine. The upstart biotech was founded in 2010, and its coronavirus vaccine will be its first authorized drug or vaccine. The company is leaning on a mix of contract manufacturers to help with different parts of the production process.

Moderna's own research hub, a 200,000-square-foot plant in Norwood, Massachusetts, will remain a core component in making the vaccine. The repurposed Polaroid plant opened in 2018 and has never been formally inspected by the FDA.

"I think the biggest risk is this is new commercial technology," Ian Leavesley, an expert in pharmaceutical manufacturing processes, told Business Insider earlier this month. "Any new technology, in any field, has a finite risk of unforeseeable risks cropping up. I believe experience is the most valuable tool in rapidly addressing this risk."

New technology set to revolutionize future vaccine research

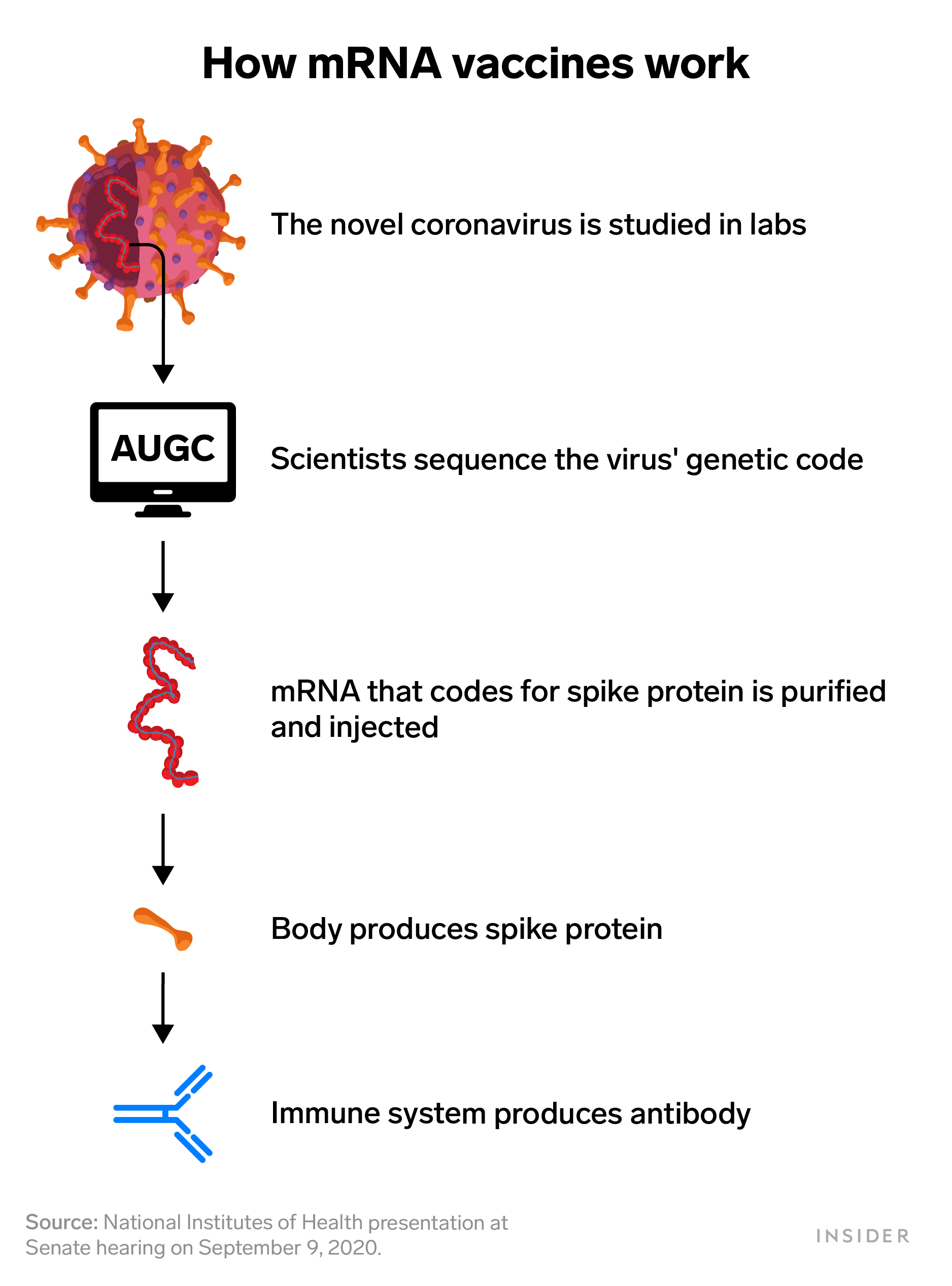

Beyond carrying the hope of turning around this pandemic, Pfizer's and Moderna's successful shots could pave the way for a revolution in vaccine development. Both shots were developed in record time using a novel technology known as messenger RNA or mRNA. mRNA is the genetic information that instructs cells how to build proteins. The new platform carries great promise but - until now - never produced an approved medicine.

Shayanne Gal/Insider

The speed of the platform could help thwart future pandemic threats, because it requires just a few days to build a vaccine candidate, using only the genetic code of a virus.

"This is not the same game," Moderna CEO Stephane Bancel previously told Business Insider. "We never saw the virus. We don't need to see the virus. What we need is the genetic instruction of the virus."

Moderna is developing other vaccines against a range of existing threats, including respiratory syncytial virus, influenza, cytomegalovirus (CMV), and the Epstein-Barr virus, which is the most common cause of mononucleosis.

"It's copy and paste," Bancel said. "So the Zika vaccine, the CMV vaccine, if this vaccine shows high efficacy, they are going to have high efficacy. It's just science."

The impact of Moderna's pandemic work has been profound, transforming the Massachusetts biotech into a high-profile member of the biotech industry.

The company commands a market value of $54 billion - up more than 600% from the start of the year - ranking alongside the most valuable companies in the industry such as Vertex, Regeneron, and Biogen.

More COVID-19 vaccines could be on the way, further boosting supply

Moderna and Pfizer are just the first vaccine programs to gain clearance in the Western world. There are more than 50 additional vaccine candidates now in clinical trials, with a handful in the final stage of research.

Johnson & Johnson, the world's largest healthcare company, is running what's likely to be the next major program that will produce definitive results. J&J recently completed enrolling more than 42,000 volunteers in its late-stage trial, which is testing giving its vaccine as both a one- and two-dose regimen. Initial effectiveness results are expected in early January.

AstraZeneca teamed up in April with University of Oxford scientists to further develop their vaccine candidate. While the duo touted initial results from some late-stage studies in November, the data was limited by a mix of research errors and poor communication. A US-based trial is likely to produce a more definitive and clear result on whether or not the vaccine works and is safe in February, Slaoui said.

Russia and China have both touted vaccines produced by their scientists, saying they are effective and safe. While those are now being rolled out within those countries, they have yet to be authorized by Western drug regulators, and the scientists haven't published late-stage clinical trial results in peer-reviewed journals.